Prelude: A Personal Perspective

As an American who has been doing business in Romania for many years, I have had the privilege of working closely with over one hundred team members across various industries. My collaborations include partnerships with some of the largest Romanian, European, and American firms operating in the country. Additionally, I have had the unique opportunity to engage with C-Suite executives from globally recognized brands and numerous American investors – some of whom remain in Romania, while others have returned to the United States. These experiences have provided me with a wealth of anecdotal insights from the “men behind the curtain,” as the expression goes, which have guided this paper’s direction.

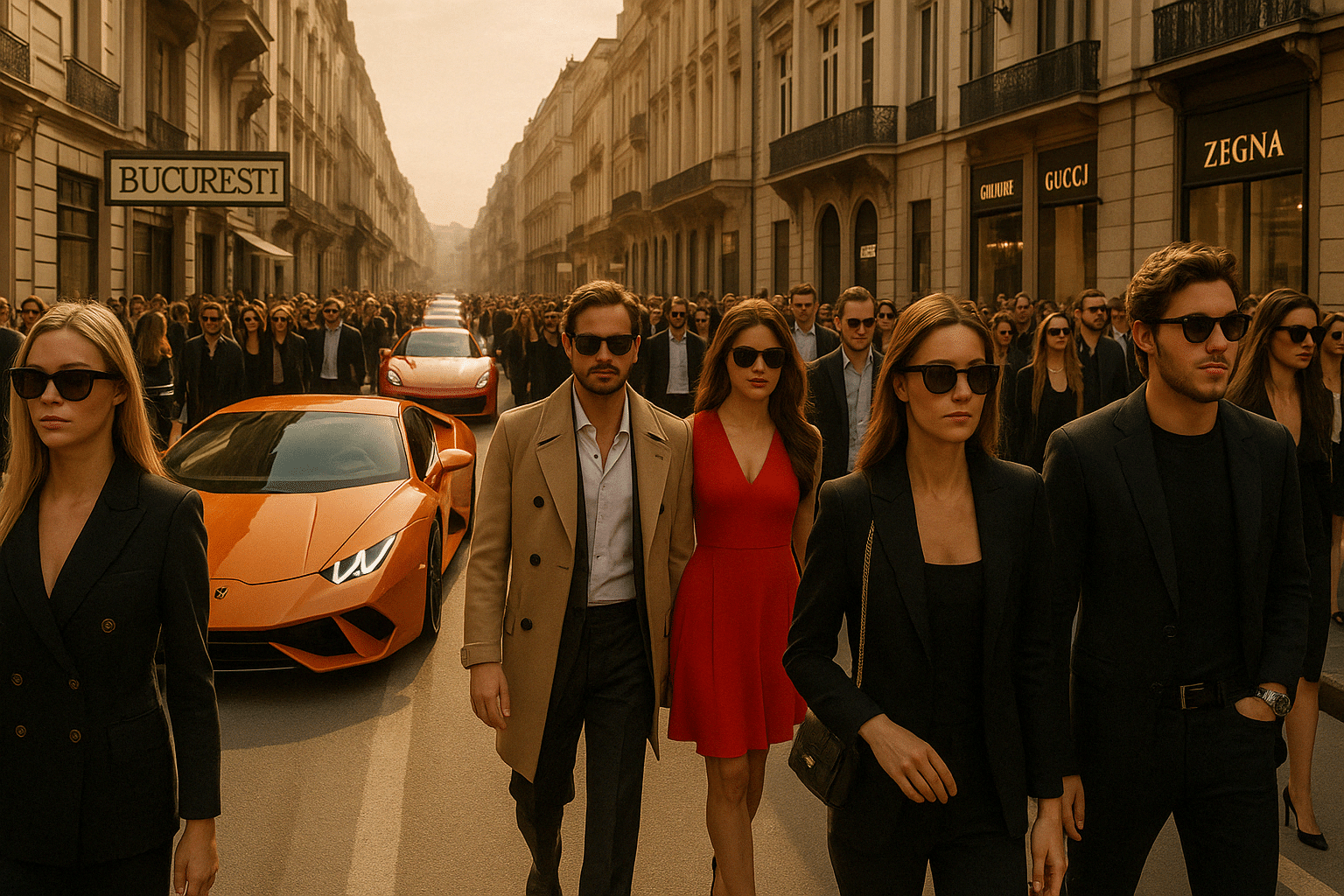

While I have endeavored to substantiate my observations with reliable third-party sources, I recognize that this remains a niche area of research. My personal travels throughout Romania, from major cities like Bucharest to remote villages, have revealed the pervasive nature of conspicuous consumption across all socioeconomic levels. This blend of professional collaboration and firsthand experience has shaped my understanding of Romania’s evolving consumer culture, allowing me to approach this topic with a nuanced perspective. Unlike in the United States, where concepts like “stealth wealth” allow individuals to underplay their financial success, Romania’s younger generations appear to embrace conspicuous consumption more enthusiastically than their elders. This is a country where wealth is often overtly displayed, and societal pressures encourage such behavior.

One notable societal trend contributing to conspicuous consumption is the phenomenon often dubbed by foreign investors as the “corporate girls” – a term that perhaps oversimplifies but reflects a recurring narrative. These are young women from rural areas who move to Bucharest for university education and subsequently immerse themselves in corporate careers, often prioritizing professional success over personal pursuits such as hobbies or relationships. By their mid-30s, many of these women express a desire to start families, leading to a perceived sense of urgency.

This dynamic, in my unsubstantiated opinion, heavily fuels conspicuous consumption on both sides: men seek to display their wealth to attract these career-driven women, while the women themselves engage in consumerism to assert their independence and success. This interplay underscores the societal pressures that drive consumption behaviors in modern Romania.

Another universal example is the use of travel as a status symbol, a trend clearly fueled by Romania’s accession to the European Union. Many Romanians aspire to work abroad in countries like Germany, France, or the UK, chasing higher incomes but often underestimating the increased cost of living and the challenges of building social networks in foreign environments. Meanwhile, domestic government jobs – criticized by many – are ironically coveted for the stability, ample time off, and financial means they provide, enabling frequent travel and luxury consumption.

Personally, I have grown weary of conspicuous consumption as an expat. I deliberately chose to live in a more modest neighborhood in Bucharest to avoid the ostentation associated with wealthier areas. In the United States, it is not uncommon for a wealthy individual to dress humbly or drive a modest car. In Romania, however, there is immense social pressure to display success through expensive cars, flashy homes, and designer clothing, often at the expense of quality. This cultural divergence has shaped my understanding of the complex and pervasive nature of conspicuous consumption in Romania.

Abstract

Conspicuous consumption, the act of purchasing goods and services for the purpose of displaying wealth and social status, has become a central topic in modern economic and sociological studies. Understanding this phenomenon offers valuable insights into how societies allocate resources, develop cultural identities, and navigate economic inequalities. In Romania, conspicuous consumption has gained relevance as the country continues its transformation from a centrally planned economy under communism to a free-market system.

Since the fall of communism in 1989, Romania has undergone significant economic and social changes, marked by liberalized markets, urbanization, and exposure to Western consumerism. These shifts have not only shaped individual consumption patterns but also redefined the nation’s cultural aspirations and societal norms. The rapid proliferation of global brands, coupled with the rise of social media platforms, has further fueled a consumer culture where material possessions are seen as indicators of success and modernity.

Examining conspicuous consumption in Romania is particularly important due to the country’s unique position as a transitioning economy within the European Union. As Romania continues to integrate with Western markets and lifestyles, the interplay between historical scarcity, economic aspirations, and cultural identity offers a compelling narrative for understanding broader trends in Eastern Europe.

Historical Context – How Did We Get Here?

Under communist rule, Romania’s consumer culture was defined by scarcity and uniformity. The availability of consumer goods was severely limited. For example, cars were priced around 70,000 lei, a staggering amount compared to the average monthly salary of just 1,800 lei – equivalent to 389 U.S. dollars today. Purchasing a vehicle often required waiting years on government-mandated lists, and basic household items were rationed by ration books.

The centralized economy prioritized heavy industry over consumer goods, leaving everyday citizens with limited access to necessities, let alone luxury items. Stores were poorly stocked, and queues for essentials were a regular part of life. Uniformity in clothing, housing, and lifestyle choices was not only a consequence of limited resources but also a deliberate effort to suppress individualism and reinforce collective identity. This era left a lasting imprint on Romanian society, fostering a mindset of resourcefulness and improvisation in the face of deprivation.

The fall of communism in 1989 marked a dramatic shift as Romania transitioned to a market economy. Much like the post-World War II transformation in the United States, Romanians experienced a sudden surge in consumer opportunities after years of deprivation and state-controlled scarcity. In the late 1940s, Americans had embraced a wave of consumerism fueled by plentiful jobs, rising wages, and an eagerness to spend after wartime restrictions. Similarly, the liberalization of Romania’s markets introduced an influx of goods and services, exposing Romanians to Western brands, advertising, and consumer culture for the first time in decades.

In postwar America, consumer spending was tied to notions of patriotism and the “good life,” with middle- and working-class families investing in products like cars, televisions, and home appliances to achieve upward mobility and modernize their lives. For Romanians, the transition carried echoes of this phenomenon, though with unique local challenges and aspirations. The availability of Western goods symbolized freedom and progress, creating a culture of aspiration similar to the American experience of the 1950s but shaped by the memory of scarcity and economic uncertainty under communism.

Among the earliest indicators of Romanian conspicuous consumption during this period was the introduction of Coca-Cola, a product that quickly transitioned from contraband to status symbol. According to the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, Coca-Cola emerged as one of the first branded consumer goods available in post-communist Romania. The product’s iconic red-and-white logo became a visible symbol of Western capitalism and modernity, signifying a “new paradigm” for Central and Eastern Europe.

In the early 1990s, Coca-Cola trucks rolling through Bucharest’s riot-torn streets were embraced as emblems of change by citizens weary from years of deprivation. The product not only symbolized freedom but also catalyzed the growth of Romania’s nascent retail sector. Small shops and kiosks used Coca-Cola to attract customers and generate capital, providing the foundation for a burgeoning entrepreneurial class.

The newfound availability of Western products generally symbolized freedom and progress, but it also created stark contrasts between those who could afford to participate in the new consumer economy and those who could not. This period saw the rise of aspirational consumption, as individuals sought to distance themselves from the hardships of the communist era by adopting Western lifestyles and symbols of success.

Moreover, the post-communist period saw rapid inflation and economic fluctuations, highlighted by Romania’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) trends. The CPI provides insight into the cost of living and price stability. According to Trading Economics, the CPI has steadily increased in recent years, reflecting the pressures of modern economic realities on consumers.

The legacy of deprivation during communism continues to shape modern consumption patterns in Romania. For many, the ability to acquire goods and services is deeply tied to notions of personal achievement and social mobility. The desire to display wealth and success through conspicuous consumption can be seen as a reaction to decades of enforced austerity. However, this cultural shift has also led to challenges, including overleveraging and consumer debt, as individuals strive to keep up with societal expectations.

Economic Framework of Conspicuous Consumption in Romania

The growth of Romania’s middle class and the country’s pronounced income inequality are critical factors driving conspicuous consumption. Romania holds the unfortunate title of being the most unequal state in the European Union, with a Gini coefficient of 35, the highest in Central and Eastern Europe. Income disparity is stark: the wealthiest 10% of Romanians earn six times more than the poorest 10%, far surpassing the EU average ratio of 3.8. This inequality fuels a culture of aspiration and competition, where individuals feel compelled to display their success to validate their place in the social hierarchy.

Romania’s GDP growth, urbanization, and increasing disposable income have also contributed to the rise of conspicuous consumption. As the economy grows and urban centers like Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca expand, more individuals have access to global brands, luxury goods, and travel opportunities. Disposable income levels, while still below Western averages, are rising, encouraging spending on items perceived as status symbols.

Remittances from Romanians working abroad play a significant role in bolstering domestic purchasing power. Many Romanians who have emigrated to countries like Germany, the UK, and Italy send money back home, enabling their families to afford higher-quality goods and services. These remittances often finance the purchase of cars, homes, and luxury items, further reinforcing a culture of conspicuous consumption. In this way, the diaspora not only contributes to the local economy but also shapes consumption patterns and societal expectations in Romania.

Credit and Financing

The availability of credit and financing has played a crucial role in enabling conspicuous consumption in Romania, particularly in the real estate market. Programs such as Prima Casa (First Home) and Noua Casa (New Home) have made home ownership more accessible, but they have also left Romanian banks overexposed to the real estate sector. These programs, often likened to the NINJA (No Income, No Job, No Assets) loans that contributed to the U.S. housing crisis, allow individuals with minimal upfront capital to enter the property market. While these initiatives have increased homeownership rates, they also raise concerns about the potential for a housing bubble and long-term economic instability.

The rising cost of real estate exacerbates this issue, as property values have increased nearly tenfold since 1989 without substantial improvements in infrastructure or amenities to justify such a surge. Romania’s extraordinarily high homeownership rate, estimated at 98%, is a direct result of post-communist policies that allowed citizens to purchase their state-provided housing at deeply discounted rates. This historical legacy has ingrained a strong cultural and emotional attachment to property ownership, with real estate often seen as a primary measure of stability and success. However, this high ownership rate has created a relatively illiquid market, with many owners unwilling to sell unless their perceived “fair” market price – often unrealistically high – is met.

This behavior is heavily influenced by the endowment effect, where people overvalue assets they own simply because they own them. In the context of Romania, this is compounded by the collective trauma of resource insecurity under communism, fostering a bias toward security and control. Landlords, particularly those who inherited properties, are reluctant to part with their assets even in a softening market. This bottleneck limits original supply for first-time buyers, further inflating costs and creating a speculative atmosphere.

In contrast to the widespread use of credit cards in Western economies, traditional consumer credit remains relatively underdeveloped in Romania. Credit cards do exist but are not widely used as a primary financial tool. Instead, alternative financing models, such as installment payment plans offered by retailers like eMag, have gained popularity. These Klarna-esque systems enable consumers to purchase electronics, appliances, and other high-value items with deferred payment options, often without requiring traditional credit checks. While this model expands purchasing power, it also creates an environment where consumers may overextend themselves financially, contributing to rising household debt.

The lack of widespread traditional credit options from banks has driven innovation in consumer financing, but it also underscores a gap in financial literacy. Many Romanians are unfamiliar with managing credit responsibly, leading to potential risks of overleveraging. Additionally, the emphasis on property ownership – often seen as a cultural aspiration and a status symbol – places further strain on personal finances, as individuals prioritize large mortgage commitments over diversified investments or savings.

Foreign Companies and Artificial Labor Rate Inflation

One of the emerging factors shaping Romania’s economic landscape – and indirectly influencing conspicuous consumption – is the influx of foreign companies and Western firms outsourcing freelance or remote jobs to Romania. While these roles are highly coveted due to their significantly higher pay compared to local wages, they also create economic disparities and distort labor market expectations.

These high-paying jobs, often concentrated in technology, finance, and consulting sectors, attract top talent, creating an exclusive workforce segment. For those employed in these positions, disposable income increases sharply, driving demand for luxury goods, real estate, and other status symbols. However, the majority of the Romanian workforce, earning local salaries, struggles to keep pace with these rising standards. This duality introduces a phenomenon of “aspirational pressure,” where individuals outside this exclusive segment feel compelled to emulate the consumption habits of their higher-earning peers, further perpetuating conspicuous consumption.

Economically, this situation ties into the concept of wage inflation and labor market segmentation. Foreign companies artificially inflate wages for skilled professionals, particularly in urban centers like Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca, creating disparities within local industries. For employers relying on local revenue streams, competing with the compensation packages offered by multinational firms becomes increasingly difficult, leading to labor shortages and skill mismatches in traditional sectors. Psychologically, this exacerbates the “relative deprivation” effect, where individuals measure their success and happiness relative to others rather than absolute standards, further fueling competitive consumption.

Moreover, the reliance on foreign investment and outsourcing introduces vulnerabilities to Romania’s economic stability. These jobs, while lucrative, are often tied to global market conditions and could be relocated if economic or geopolitical circumstances shift. This reliance also detracts from developing sustainable local industries that could provide broader economic opportunities. In the meantime, the exclusivity of these positions reinforces conspicuous consumption behaviors, as the competition for social validation intensifies in a segmented labor market.

The Role of Social Media in Amplifying Conspicuous Consumption

The digital age has dramatically accelerated the spread and normalization of conspicuous consumption in Romania, particularly among younger demographics. Social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook have become central to personal branding and social validation, turning lifestyles into curated performances. What one wears, where one vacations, and even what one eats are now commodified experiences, strategically shared to signal status and sophistication.

This phenomenon is especially visible among Romanian influencers and micro-influencers, whose follower bases often measure in the tens or hundreds of thousands. Many of these individuals promote luxury goods and services – frequently through undisclosed sponsorships – creating unrealistic lifestyle expectations for their audiences. Unlike the United States, where influencer culture is increasingly regulated and scrutinized, Romania’s digital consumer environment remains relatively under-policed. This has contributed to a Wild West-style landscape where ostentatious displays are not only common but encouraged.

Romania’s Gen Z and Millennial cohorts have grown up in a starkly different world than their parents. Unlike the generations raised under communism, today’s youth have been shaped by EU integration, digital globalization, and liberalized consumer markets. This shift has cultivated a generation that is simultaneously more aspirational and more burdened.

As a result of these countless factors, many young Romanians perceive material success as not only a goal but an obligation – one that validates their migration from rural towns to urban centers and justifies years of academic and career investment. Yet, as housing costs, inflation, and job insecurity rise, this ideal becomes increasingly elusive.

The Myth of Meritocracy

Beneath Romania’s modern consumer culture lies a complex set of cultural paradoxes. On one hand, there is an increasing emphasis on meritocracy and upward mobility, especially among the urban middle class. Success is portrayed as achievable through education, hard work, and networking, which are principles reinforced by Western business norms and aspirational media narratives. On the other hand, Romania still grapples with entrenched nepotism, opaque hiring practices, and limited social mobility in many sectors.

This disconnect breeds cynicism, particularly among the educated youth who pursue elite degrees or international certifications, only to discover that job opportunities often hinge on personal connections rather than merit. The resulting frustration can fuel even more ostentatious consumption, as individuals seek to differentiate themselves and “play the part” of success in hopes of finally being noticed or included in Romania’s increasingly image-driven professional circles.

In rural areas, these paradoxes are even more pronounced. Families frequently make significant financial sacrifices to support a child’s education or overseas employment, viewing their eventual return with material success as a collective triumph. This explains, in part, the cultural importance of weddings, home renovations, and imported vehicles in rural Romania; not just as personal milestones, but as public declarations of having “made it.”

Toward a More Sustainable Consumer Culture?

Despite the dominance of conspicuous consumption, there are signs of gradual cultural evolution. Romania’s emerging entrepreneurial class, especially those operating in digital and creative industries, are beginning to embrace alternative values: minimalist lifestyles, ethical consumerism, and investments in personal development over material display. Environmental concerns and economic pressures are also prompting some Romanians, particularly in cities like Cluj-Napoca, Iași, and Bucharest, to rethink the cost-benefit ratio of constant consumption.

Still, such changes face strong headwinds from entrenched social expectations and commercial advertising that continues to glorify material success. The challenge for Romania moving forward is whether it can balance the desire for Western-style prosperity with a deeper, more authentic understanding of what constitutes a meaningful and stable life. As Romania continues to navigate its identity within the European project, the question remains: will consumption continue to define success, or can new values emerge to shape a more grounded national ethos?