Global connectivity has made it easier than ever to work from virtually anywhere, identifying which countries present the best opportunities – especially in emerging economies – can be both exciting and daunting. Traditional measures like GDP or average income only scratch the surface when deciding whether to relocate or launch a venture abroad.

This article proposes a structured method to compare multiple countries based on a range of economic and infrastructural variables, called the Opportunity Score. It aims to guide entrepreneurs, digital nomads, and investors toward informed decisions about where to base themselves or their businesses.

In many ways, the framework outlined here mirrors how I personally concluded that Romania offered greater upside for my goals compared to remaining in the United States.

Why a Systematic Comparison Is Essential

When individuals consider relocating to an emerging economy, they often fixate on one or two factors: typically, lower living costs or more relaxed regulations. However, such a narrow focus can miss the bigger picture. A place with cheap rent but limited market access may fail to deliver on income potential. A country with enticing tax benefits might suffer from a shortage of skilled talent, reducing the feasibility of scaling a business. Emerging economies, by their very nature, offer unique advantages, like untapped markets and relatively lax competition, while also posing challenges such as bureaucratic hurdles and infrastructural gaps.

A systematic, formula-based comparison can mitigate the risks of relying on hearsay or single metrics. By assigning numerical values to both “hard” variables (like tax rates or PPP-adjusted income) and “soft” variables (like the talent pool or cultural attitudes toward entrepreneurship), prospective expats or entrepreneurs gain a more holistic understanding of what to expect. It ensures that moving to an emerging market – Romania, Serbia, Colombia, or otherwise – is a conscious strategic choice rather than a leap of faith.

Proposed Formula

Sub-Formula 1: Net Income Potential

The first building block of the Opportunity Score is Net Income Potential, encapsulating the realistic amount of money you stand to earn after key deductions and adjustments.

![]()

: Gross income potential in Country

: Gross income potential in Country  (this could be your salary, freelance revenue, or projected business profits).

(this could be your salary, freelance revenue, or projected business profits). : Subtract the effective tax rate

: Subtract the effective tax rate  (encompassing income taxes, social contributions, etc.).

(encompassing income taxes, social contributions, etc.). : A multiplier capturing how easy or complex the tax system is. If you benefit from strong tax incentives, this might be > 1; if red tape eats away at your net, it might be < 1. In plain English, tax rates don’t tell the whole story; so, we factor in Tax Complexity – a measure of how quickly paperwork can bog down your earnings or, conversely, how certain tax incentives might boost your net.

: A multiplier capturing how easy or complex the tax system is. If you benefit from strong tax incentives, this might be > 1; if red tape eats away at your net, it might be < 1. In plain English, tax rates don’t tell the whole story; so, we factor in Tax Complexity – a measure of how quickly paperwork can bog down your earnings or, conversely, how certain tax incentives might boost your net. : A factor that adjusts nominal figures according to purchasing power parity. This ensures your “real” earnings in local currency reflect what they can buy, relative to a standard like USD.

: A factor that adjusts nominal figures according to purchasing power parity. This ensures your “real” earnings in local currency reflect what they can buy, relative to a standard like USD.

Why is this step so crucial? In many emerging economies, tax policies and incentives can be quite different, and sometimes surprisingly advantageous, compared to developed countries.

For instance, Romania offers certain tax breaks for IT workers, which can dramatically affect net income. Additionally, PPP adjustments often reveal that an apparent “low” salary in an emerging market might, in fact, stretch further in day-to-day expenses than a nominally higher salary in a developed nation.

By compressing all these intricacies into one sub-formula, NetPotential(C), we get a snapshot of your real earning capacity within that specific country.

Sub-Formula 2: Enabler Factors

Next, we combine the qualitative and structural elements that can boost or dampen your success. These are consolidated into a product called Enablers(C):

![]()

Each term is a multiplier:

(Ease of Doing Business): Reflects bureaucracy, speed of forming a company, and overall administrative hurdles.

(Ease of Doing Business): Reflects bureaucracy, speed of forming a company, and overall administrative hurdles. (Risk Factor): Economic and political stability. A stable country might score above 1, a volatile one below 1.

(Risk Factor): Economic and political stability. A stable country might score above 1, a volatile one below 1. : Availability of skilled workers in your sector.

: Availability of skilled workers in your sector. : Readiness of banks, VCs, and investors to fund new ventures.

: Readiness of banks, VCs, and investors to fund new ventures. : Quality of the legal system, contract enforcement, corruption levels, IP protection, etc.

: Quality of the legal system, contract enforcement, corruption levels, IP protection, etc. : Cultural attitudes toward entrepreneurship (stigmatized, supported, or neutral).

: Cultural attitudes toward entrepreneurship (stigmatized, supported, or neutral). (Infrastructure & Ecosystem): Overall maturity of industry or potential “greenfield” gaps you can exploit.

(Infrastructure & Ecosystem): Overall maturity of industry or potential “greenfield” gaps you can exploit. : Internet speeds, digital payment penetration, and other connectivity measures.

: Internet speeds, digital payment penetration, and other connectivity measures. : Stability and consistency of government policies.

: Stability and consistency of government policies. : Convenient overlap with major markets or team members.

: Convenient overlap with major markets or team members. : Likelihood of currency fluctuations or sudden devaluations.

: Likelihood of currency fluctuations or sudden devaluations.

If you’re considering an emerging economy, you might see unusually high multipliers in some categories, say, a rapidly improving ecosystem or a highly supportive entrepreneurial culture, even as other categories lag. One example in Romania is the TechConnect factor: the country’s internet speeds are among the highest in Europe, which can significantly ease digital business operations.

Avoiding Subjectiveness and Pre-Existing Biases in Enabler Factors

Measuring enabler factors can feel subjective at first, so it helps to define specific metrics or data sources for each. The goal is to score each factor on a consistent scale, typically from 0.0 (extremely disadvantageous) to 2.0 (extremely advantageous), with 1.0 representing a neutral or “average” baseline.

As a potential starting point:

Ease of Doing Business

How to Score: Convert the country’s percentile ranking into a 0–2 scale. For example, if it’s in the top 10% globally, it might score 1.8–2.0; if it’s around the midpoint, 1.0, and if near the bottom, 0.5 or lower.

Suggested Data Source: World Bank’s “Ease of Doing Business” ranking, or any reputable index that measures bureaucratic efficiency.

Risk Factor

Suggested Data Source: Political and economic risk indices from institutions like the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) or International Country Risk Guide (ICRG).

How to Score: A stable, low-risk country might be 1.2–1.5; if political upheaval or economic volatility is high, it could drop to 0.7 or below. You can also incorporate currency volatility into this if you don’t treat it separately.

Talent Pool

Suggested Data Points:

- Number of STEM graduates per capita.

- Penetration of English or other key languages in the workforce.

- Rankings of local universities or coding bootcamps.

How to Score: If you confirm a robust talent pipeline (e.g., large engineering schools, strong English proficiency), you might rate 1.3–1.5. A shortage of specialized skills or a language barrier could push it down toward 0.8 or less.

Capital Availability

Suggested Data Source: VC investment volumes, angel networks, or governmental grants/funding programs. You can look at local deal flow data (e.g., from Crunchbase or Dealroom).

How to Score: If the ecosystem has multiple active funds and frequent seed rounds, you might set this above 1.0. If virtually no local funding is available, it could be 0.5 or below, unless you plan to raise internationally (in which case local availability matters less).

Regulatory & Legal Environment

Suggested Data Points:

- Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index.

- World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index.

- Contract enforcement time/cost data from legal studies.

How to Score: If corruption is low and courts enforce contracts reliably, 1.0–1.2 makes sense. With pervasive corruption or unpredictable courts, it could drop to 0.6 or lower.

Cultural Attitudes Toward Entrepreneurship

Suggested Qualitative Measures:

- Number of startup incubators, co-working spaces, entrepreneurial meetups.

- Survey data indicating whether locals view entrepreneurship favorably.

How to Score: If there’s a strong startup culture (e.g., frequent hackathons, supportive media coverage), you might go 1.2 or higher. If risk-taking is stigmatized or entrepreneurial activity is rare, closer to 0.8 or below.

Infrastructure & Ecosystem

Suggested Data Points:

- Quality of roads, ports, logistics.

- Availability of manufacturing partners or supply chains if relevant.

- Presence of complementary industries (e.g., a strong fintech ecosystem if you’re launching a finance app).

How to Score: A well-developed network of suppliers and partners could rate 1.2–1.4. If the infrastructure is underdeveloped yet offers “first-mover” advantages, you might weigh that as a positive – still potentially 1.0+. If the gap is a severe handicap, it could be 0.7 or lower.

Technology & Connectivity

Suggested Data Points:

- Average internet speed (e.g., Ookla Speedtest global rankings).

- Mobile broadband penetration rates.

- Adoption rates for digital payments or e-commerce.

How to Score: A top-tier internet infrastructure can earn 1.2–1.5, while highly limited connectivity might rate below 1.0.

Government Stability

Suggested Data Source:

- Political stability indexes (e.g., The Global Peace Index).

- Frequency of policy changes or governmental turnover.

How to Score: A historically stable government with predictable policy might be 1.2–1.3. An environment prone to abrupt regime changes or policy swings could be 0.7 or lower.

Time Zone Alignment

Suggested Assessment:

- Overlap with your main clients, your remote teams, or key investors.

How to Score: If the time zone is perfectly aligned with your key market (e.g., within 1–2 hours), you might assign up to 1.3. If it causes daily communication hurdles, you’d adjust downward.

Currency Stability

Suggested Data Points:

- Historical exchange rate volatility against major currencies (USD, EUR).

- Inflation rates and central bank policies.

How to Score: If the currency is pegged to a stable standard or has minimal fluctuations, consider 1.1–1.2. If historically it’s fluctuated significantly, you might rate it 0.8 or lower.

Sub-Formula 3: Net Cost (PPP-Adjusted)

No assessment is complete without acknowledging how much you spend to maintain a baseline lifestyle or run a business. We define:

![]()

: Typical monthly or annual expenses for housing, transportation, food, utilities, plus any recurring business costs.

: Typical monthly or annual expenses for housing, transportation, food, utilities, plus any recurring business costs. : The same purchasing power factor ensures we’re consistently comparing “real” costs between countries.

: The same purchasing power factor ensures we’re consistently comparing “real” costs between countries.

Notably, emerging economies often have lower living expenses – one of the major draws for foreigners. Yet, certain specialized services or imports can be surprisingly costly, so it’s crucial to do your homework. Simply labeling a country “cheap” can be misleading if, for instance, you need to import specialized equipment or rely on high-end labor. Nevertheless, if local living costs remain substantially lower than in a high-cost environment like the United States, NetCost(C) can be a fraction of what you’d expect back home.

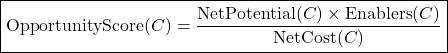

Putting It All Together: The Opportunity Score

After defining these three sub-formulas, the final expression is elegant:

Where:

A higher overall score suggests that the country offers a more efficient pathway to building wealth or a thriving business, once you weigh both the positive factors (like a strong talent pool or good infrastructure) and the negative constraints (like taxes or regulatory hurdles).

You can compare countries by calculating the Opportunity Score for each, then looking at the difference:

![]()

A positive ![]() indicates Country A outperforms B under your chosen assumptions; a negative

indicates Country A outperforms B under your chosen assumptions; a negative ![]() implies the opposite.

implies the opposite.

How This Differs from PESTLE and Other Traditional Analyses

Although it may resemble PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, and Environmental analysis) at first glance, the Opportunity Score framework serves a different purpose and is structured to provide more precise quantitative comparisons. PESTLE, by design, organizes environmental scanning into broad categories and typically offers qualitative insights—an overview of potential risks and opportunities—without arriving at a single numeric measure. In contrast, the Opportunity Score formula requires assigning specific numeric values to variables like tax rates, talent pools, or cost-of-living factors. This yields a direct, comparable metric that can be recalculated as local conditions shift.

Moreover, PESTLE is often used as a higher-level snapshot, suitable for shaping a wide-ranging strategic outlook rather than focusing on an individual’s or venture’s bottom line. While PESTLE might note currency fluctuations and legal complexities, it doesn’t necessarily integrate purchasing power parity in relation to your personal or business finances. The Opportunity Score, on the other hand, explicitly incorporates PPP to show how net income potential stacks up against local expenses—making it especially valuable for entrepreneurs, digital nomads, or small businesses seeking tangible indicators of financial feasibility.

Another key distinction is the weighting mechanism. PESTLE frames issues like political stability or social attitudes as qualitative considerations, which are important for strategic decision-making but do not always provide clear, quantifiable outcomes. In the Opportunity Score, each factor – whether it’s cultural acceptance of entrepreneurship or the reliability of local banks – can be assigned a value above or below 1.0, allowing for a fine-tuned, numeric balance of benefits and drawbacks. This helps users prioritize what matters most in their specific context, rather than merely listing concerns.

Additionally, PESTLE tends to be a one-time audit, giving an overview that might not be updated frequently unless a major event occurs. The Opportunity Score method can be repeatedly recalibrated as new data comes in, reflecting shifts in a country’s tax policy, cost of capital, or infrastructure quality. That makes it a living tool, easily adaptable to dynamic environments where conditions often change faster than static analyses can keep up.

Conclusion

In closing, the Opportunity Score methodology offers a structured, data-informed way to compare different countries for entrepreneurial or personal ventures. It breaks down complex elements – income potential, enabler factors, and net costs into a clear numeric model. This balance of quantitative rigor and flexible inputs sets it apart from broader frameworks, ensuring that each variable (from local tax incentives to the cultural acceptance of startups) is fully accounted for in the final calculation.